While often thought of as a process limiting movement undertaken by a particular nation, incarceration is actually a process filled with mobility and international relationships.

Some US states collaborate with other nations around the globe to outfit their corrections department and make money showing off facilities and practices to their correctional officers. For example, Maryland’s Department of Safety and Correctional Services (DPSCS) can be identified as a key actor in the importation and exportation of policing practices, policies and officers.

The criminal-legal system presently exists as a system endeavored toward mass human detention bound up in different dynamics of labor, consumption and financialization. With the most incarcerated per capita in the world, The United States of America is frequently identified as the global capital of incarceration. This mass project of detention means different US states and their correctional departments collaborate with other nations to showcase different detention methods, labor organizations and facilities.

Maryland as a Site of International Carceral Exchange

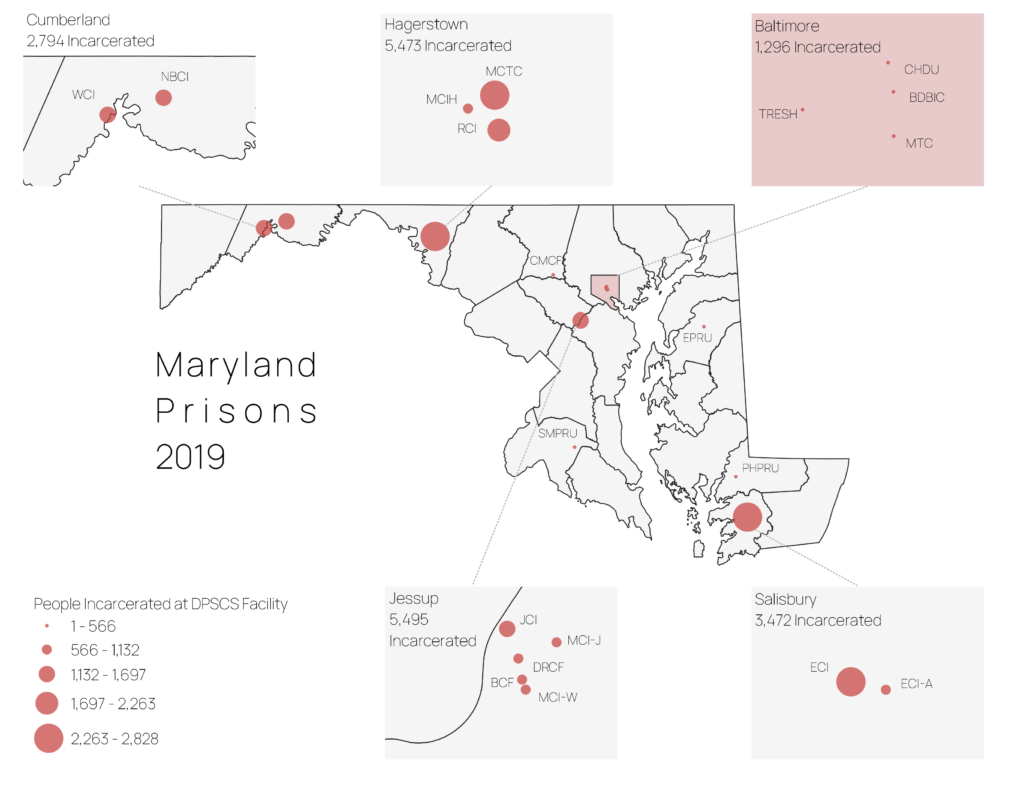

Maryland’s Department of Public Safety and Correctional Services (DPSCS) was founded in 1970, subsuming various correctional entities that had been active in Maryland since the 1800s (Maryland State Archives). DPSCS currently operates 19 institutions placed in about 8 general localities around the state (DPSCS). These facilities detain approximately 18,000 people on site, but the number of people under their correctional surveillance–inclusive of house arrest, parole, probation, etc – exceeds 40,000 on any given day. DPSCS has an annual budget of around 1 billion dollars and almost 12,000 employees (DPSCS). Recently, in order to maximize the number of hires and increase profitability, MD DPSCS has started different recruitment and training programs with countries outside the US.

International Correctional Bed and Breakfast?

In 2011, MD DPSCS signed an agreement to “train leaders of Mexico’s state-level Model Police Units (MPUs).” An MPU is a 422 person police force that was ostensibly formed to address drug trafficking in Mexico (Office of the Spokesperson, 2011). Mexico was planning on having at least 32 MPUs, translating to a force of over 13,000 Mexican officers trained through the Maryland DPSCS. Before 2011, MD DPSCS was already training officers from Mexico and participated in exchange programs with other countries. Importantly, the state department mentions that this agreement is actually only the beginning of collaboration between the state department, international federal governments, and DPSCS (Office of Spokesperson, 2011).

Mexico was planning on having at least 32 MPUs, translating to a force of over 13,000 Mexican officers, trained through the Maryland DPSCS.

Data Source: DPSCS Operations FY2019

On YouTube, the MD DPSCS has a set of videos part of a series called “Inside the Fence and Beyond” which aim to show the public the inner workings of the DPSCS. These videos have a cheery and uplifting tone, aiming to parade around new technologies, practices, and “restorative justice” those incarcerated in Maryland must engage in as part of their “rehabilitation” while incarcerated (MDDeptPublicSafety, 2017).

In Carroll County, one of the DPSCS facilities is located at the former Springfield State Hospital Center. This particular facility is used as the Public Safety Training and Education Center – or what DPSCS spokesman Mark Vernarelli called “the seat of Law Enforcement Training for the entire state of Maryland,”. Local law enforcement, correctional officers, and probation officers are all trained at the former State Hospital Center. Importantly, this facility was one of the 12 Maryland Psychiatric hospitals which detained individuals. This is where every officer in Maryland was trained, but it is also where officers from around the globe travel to be trained.

In an “Inside the Fence and Beyond” episode, Rene Gonzales, a correctional officer from Mexico discusses how he learned how to properly grip an incarcerated person to limit their ability to resist forced movement with a tactic called the “c-grip” (MDDeptPublicSafety, 2017). The Women’s only correctional facility located in Jessup also hosted groups from China and Mexico in 2017. On their YouTube channel, DPSCS not only showcases how they train correctional officers, but they also showcase the labor process of Maryland Correctional Enterprises (MCE). MCE is the state prison industry arm through which prison labor is formally conducted and commodities are produced for state organizations and nonprofits.

Maryland’s prisons are the site of diffusion of carceral techniques and practices at multiple scales: for the state, the nation, and internationally. These programs where officers from other countries travel to Maryland facilities and stay with trainers here for days or weeks are funded by the federal governments of the United States and the other country involved. In this way, the MD DPSCS accumulates money and resources from different nations through the commodification of carceral techniques. Maryland DPSCS showcases how they run their prison labor project. Specifically, Maryland shows other states and nations how prison labor is conducted under Maryland’s state model- a correctional enterprise controlled by the state which sells commodities to state facilities and nonprofit organizations. In 2019, MCE made $52,457,137 dollars in sales with 1,516 working incarcerated people (Maryland Correctional Enterprises, 2019).

Recruiting Correctional Officers Beyond Borders

Image Source: DPSCS Facebook

DPSCS’ large budget and a restructuring of the recruitment process meant looking beyond Maryland for correctional officers. It is noted at certain correctional officer training graduation ceremonies that the department has been having a very difficult time recruiting people who want to work in corrections, despite the vast number of benefits and guaranteed salary for those who do sign up to enforce the caging of human beings for a living.

In 2019 the department hired a new head of recruitment. At the 2020 Correctional Officer (CO) training graduation ceremony, attorney and director of human resources for Maryland DPSCS Sasha Vazquez-Gonzalez was described as someone who understands “the flow of how she has to hire people in this climate where public safety agencies nationwide are struggling to hire people,” and her efforts in recruiting were described as “novel” and “very interesting” (MDDeptPublicSafety, 2020). What were her novel recruitment ideas?

One idea was a pilot project to recruit new COs from Puerto Rico. When she presented the idea for the program, Vazquez-Gonzalez described feeling amazed when DPSCS executive leadership welcomed the idea with open arms. Under her leadership, Maryland DPSCS traveled outside the continental U.S. for the first time to recruit correctional officers. The program was successful and was expanded to recruit non-Marylanders abroad. This strategy has now become “a day-to-day operation for correctional officer recruitment” (MDDeptPublicSafety, 2020). In the video, she states, “Look around. You might notice that this is one of the most diverse classes ever.” They “represent the appreciation for diversity we have in this department.”

In 2020 Maryland’s Department of Corrections and Public Services graduated officers with homelands of Puerto Rico, Trinidad and Tobago, Dominican Republic, Bermuda, Cameroon, the Bahamas, Nigeria, Ghana, Guatemala, Sierra Leone. The graduated officers often immigrated specifically to work in the DPSCS or were recruited by Maryland’s DPSCS in their home country. Vazquez-Gonzalez concludes her remarks for the first graduating class of 2020 with “we are all public safety” (MDDeptPublicSafety, 2020).

Interrogating these Global Collaborations

The Maryland DPSCS is emerging as a key actor in the importation and exportation of policing practices, policies and officers. The department has actively recruited in many countries which make up an area in the neo-colonial Atlantic sometimes referred to as “the West Indies”. The DPSCS has hosted other visiting correctional staff from outside the U.S. to show off Maryland correctional facilities and train other countries’ correctional officers. Maryland’s correctional facilities are global sites of exchange for carceral techniques and expertise. They have become a key agent in the global production of carceral space.

The places of importation and exportation of criminal legal techniques, practices and people are also entangled with the colonial history of these spaces.

The places of importation and exportation of criminal legal techniques, practices and people are also entangled with the colonial history of these spaces. These dynamics are historically contingent. Maryland is not actively recruiting for correctional officers in the UK. The US is not learning about best policing practices from Vietnam. The particular flows have been produced through rounds of exploitation and violence and are bound up in the imperialist present. As an imperialist actor, the US State Department facilitates carceral exchange which aids in profit accumulation. Like the exchange of commodities and capital, the exchange, exportation, importation of carceral techniques, practices, and officers makes carceral capitalism a global project.

From this preliminary look at Maryland’s DPSCS many more questions emerge: What particular techniques and policies are imported and exported? More research should be conducted so that a comprehensive understanding of Maryland’s DPCPS international relationships can be established. We should all pay attention to this move toward international efforts for recruitment and efforts toward the international standards for correctional and policing practices in the MD DPSCS. DPSCS have perhaps discovered that instead of increasing the salary or benefits for correctional officer positions to make them competitive to Maryland residents or those in the continental U.S., it is possible to change the location of who they are offering the salary and benefits to. What kinds of implications does this international carceral labor program have?

With the mapping.capital research collaborative and on my own forthcoming website I hope to uncover and interrogate how capital leverages carceral practices and technologies to further profit accumulation and produce uneven geographies.

This blog post was adapted from a paper called “Maryland as a Locus of International Criminal-Legal Exchange” which I wrote for a Graduate Seminar Logics of Capital taught in Fall 2021 by Dr. Dillon Mahmoudi. Please reach out to the author for the full paper.

References

Maryland Correctional Enterprises. (2019). Annual Report FY2019. Retrieved from https://www.dpscs.state.md.us/publicinfo/publications/annuals.shtml

Maryland Department of Safety and Correctional Services. (n.d.) About DPSCS. Retrieved from https://dpscs.maryland.gov/about/

Maryland Department of Safety and Correctional Services. (n.d.). DPSCS Annual Data Dashboard. Retrieved from https://www.dpscs.state.md.us/community_releases/DPSCS-Annual-Data-Dashboard.shtml

Maryland Department of Safety and Correctional Services. (2019). Operations. Retrieved from https://www.dpscs.state.md.us/publicinfo/publications/annuals.shtml

Maryland State Archives. (n.d.). Department of Safety and Correctional Services: Origin. Retrieved from https://msa.maryland.gov/msa/mdmanual/22dpscs/html/dpscsf.html

MDDeptPublicSafety. (2020). Maryland Correctional Class 20-01 Graduation https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_qIncQJwCMs

MDDeptPublicSafety. (September 5, 2017). DPSCS Inside the Fence and Beyond- Episode 2. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7QLbJOyTo3o&t=436s

Office of the Spokesperson. (2011). Maryland’s Department of Public Safety and Correctional Services Will Assist Mexico’s Federal Police in Training Leaders of Mexico’s State-Level Model Police Units. Retrieved from https://2009-2017.state.gov/r/pa/prs/ps/2011/10/175544.htm

Leave a Reply